Accidental advocate

Four years ago, I published a memoir about taking care of my Schizophrenic brother. When I was working on the book (Shot in the Head, a Sister’s Memoir, a Brother’s Struggle), I did research into national statistics on mental illness, and I was horrified. My family had always thought the poor care my brother received was a horrible mistake. We thought that his social workers must not have realized that the modern psychotropic medications—reputed to virtually cure psychosis—didn’t really help him. They must not have realized that he needed to live in sheltered, supervised housing, not be expected to take care of himself. But, to the contrary, we found this abandonment of people with serious mental illnesses (SMI) to be a nationwide scourge. He was one of hundreds of thousands, even millions of people suffering from serious mental illness, abandoned by the country’s mental health system, destined to a miserable half life of delusions, homelessness and victimization. More than one percent of our population suffers from schizophrenia (that’s over 3 million people), and more than half of them need the kind of care my brother needed. And they’re not getting it.

Most people with a serious mental illness cannot keep a job. Their families often try their best to help them, but they simply can’t handle them when they’re as difficult as my brother. They depend on social services, notably Medicaid, for health care coverage. Medicaid does a decent job of providing medical care to the least fortunate of our fellow citizens if they suffer from diabetes or bronchitis, cancer or eye infections. Medicaid pays for their care for physical ailments, even if it involves a multi-week stay in a hospital. But Medicaid funds, from its inception in the mid 1960’s, were barred from caring for people with a psychiatric illness on an inpatient basis. The legislation prohibits its use in the treatment of adults (persons between the ages of 21 and 64) in facilities having more than 16 beds for the specific treatment of mental disorders, a.k.a. institutions for mental disease (IMD). It also effectively prevents the management of long term supervised housing for people whose mental disabilities prevent them from living independently.

Congress included coverage for Alzheimer’s disease and intellectual disabilities in Medicaid legislation; many of us have a grandmother or other senior relative being cared for in a nursing home because of their dementia, the care being paid for by Medicaid. But when the Medicaid legislation was passed there was a concern that if IMD’s were included in the Medicaid program, the states would continue to warehouse people in hospitals instead of providing services in the community, which was their goal. That reasoning has not lived up to the promise, however. Without funding, most IMD’s have closed. Yet communities have failed to provide adequate comprehensive community-based services to take their place, leaving those with serious mental illnesses without adequate care. No institutions are helping families care for their seriously mentally ill loved ones anymore. Those who are ill are ferried into ERs, then released with a bottle of pills and no real help—if they are lucky. In many cases, they end up in prison, or shot by police called to help the family when their loved one is acting out.

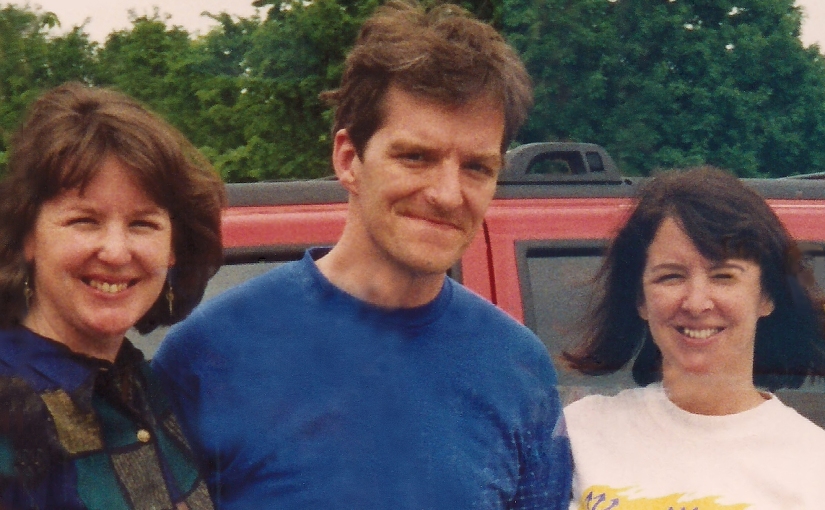

My brother Paul, luckily, never ended up in jail or shot by police, but he was given desultory care, at best. He was too dangerous for us to let him live at home with us, yet the “adult homes” he was placed in were inadequate for the severity of his symptoms.

I determined that this had to change. I joined up with organizations of family members like me who were lobbying Washington DC for improved care practices. Organizations like the Treatment Advocacy Center, and advocates from Baltimore, Sacramento & Los Angeles, New Orleans—all over the United States. And things have begun to change. With the implementation of the 20th Century Cures Act last year, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Agency (SAMHSA) has a new, cabinet level head of the subagency that deals with serious mental illness, and they are revamping its activities to make sure those who are most seriously ill get the treatment they need. I now serve on the communications committee of the National Shattering the Silence Coalition, an organization of activist like my self who are fighting to have the IMD exclusion to Medicaid repealed.

There is much more work to be done.

And now I have added another cause to my advocacy, another response to my writing.

When my teenaged nephew died of a heroin overdose, I had no intention of getting involved in any further advocacy work. I wrote the poetry which eventually became my chapbook, Aftermath, from my sense of sorrow, not with any didactic interests. I found I had to slow down and let the grief sink in. Everything I saw around me was tinged with loss. I had to make sense of this, and of the changed circumstances of my family. When more sorrows arose—the deaths of two people close to me—it compounded my grief. The collection became a kind of meditation on loss and a search for renewal.

Yet again, I have found myself immersed in advocacy. I am appalled at the greed and ineptitude that have contributed to the opioid crisis. I am mystified at how little current treatment standards do to help people with substance use disorder (SUD) overcome their addiction and move on to a productive life. I now speak out for tighter regulation to hold rehab centers accountable for the efficacy of their practices, including evidence- based practices for rehab treatment. And I encourage efforts to hold accountable the drug companies whose aggressive marketing of drugs like OxyContin contributed to the crisis.

The news is filled with articles about lives lost to opiates. West Virginia and Kentucky may be the epicenter of the plague, but no town in the U. S. has escaped the scourge. About 75,000 people died of an opiate overdose in the past year. We also, all too often, are horrified to read about yet another mass shooting, many of them involving a shooter with untreated mental illness. And for every life lost, an entire family suffers.

Congress appears to have come to the realization that the IMD exclusion is preventing the funding of care for people trying to overcome their SUD, as well as those with a SMI. So people who cannot afford inpatient care try to deal with their issues using outpatient services. There is legislation in the works that may, at least temporarily, allow Medicaid funds to pay for up to a month of in-patient treatment. The legislation is incomplete, however, as it does not take into account how many people with SUD are also suffering from a severe mental illness. Both conditions need inpatient medical care, using verified treatment methods and holding the treatment facility accountable for statistically positive results.

I speak out whatever chance I get about the need for better treatment of both SUD and SMI. (I’m becoming a master at acronyms!) All kidding aside, I am reminded of the parable of the Good Samaritan, who found a man from another town beaten and robbed in a ditch. He took the man home and nursed him back to health. Growing up, we were taught that we must care for people who suffer, help them back on their feet. I guess the lessons sunk in.

One of my poems in Aftermath includes the lines:

Even then you and I sensed this could happen only once. Our lives/

would now have a before and after.

Caring for my brother was an experience like that. Losing my nephew was an experience like that. Sometimes we go through a difficult time in our life and we are changed. In my case, I became – quite by accident – an advocate.

***

Katherine Flannery Dering is a writer and mental health advocate and serves on the communications committee of the Shattering the Silence Coalition, (http://www.nationalshatteringsilencecoalition.org) an organization that seeks to highlight the need for better care for the millions of people suffering from serious brain disorders. She believes words can effect change, and she hopes her words help in this effort. She also blogs on behalf of sensible controls over illegal opiates and results-proven rehab programs.

Her chapbook, Aftermath, began during the weeks following the death of her teenage nephew from a drug overdose. During the ensuing months, two other close friends died, as well. This collection is, in part, reflections on the question, How do I make sense of my life in the face of death’s inevitability? How do any of us? She empathizes with other victims of the country’s opioid epidemic and encourages family survivors to speak out for better, evidenced-based treatment. These poems delve into the sorrow of losing someone to drug addiction and asks the question, where do I go from here?

Ms. Dering has lived in Westchester county, New York for over thirty years. Currently, she serves on the executive committee of the Katonah Poetry Series, is on the board of the local chapter of the League of Women Voters, and is an active member of the Pound Ridge Authors Society. She blogs at www.deringkatherine.wordpress.com. Visit her website at www.katherineflannerydering.com. Her chapbook, Aftermath, is available at https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/aftermath-by-katherine-flannery-dering/ and at Amazon. Her memoir, Shot in the Head, A Sister’s Memoir, a Brother’s Struggle is available at Amazon.