About five months after my family moved to Switzerland in 1959, my mother went into labor early, with what we thought would be her eighth child. After three weeks of complete bed rest, the surprise twin babies – eighth and ninth – were born Christmas Day.

How auspicious! Paul was so beautiful, with his blond curls and long, lanky body! Even his fingers were long and elegant. Ilene, two pounds smaller than Paul, was tiny and had straight dark hair and intense dark eyes set into a little round face. She looked like the Japanese dolls friends had sent us from Japan in the early ’50’s.

The twins were baptized a few weeks later in a tiny, Medieval stone church in the nearby town of Versoix, each of them dressed in a piece of the Christening gown my father and the older seven children had been baptized in. My older sister Sheila and I (first and second of the brood) held them for the service, filling in for the official godparents, who were back in the States.

On Christmas mornings, for all the years that the twins were growing up, the ten of us kids (our tenth – and last – child, Julia, was born two years after the twins) woke before dawn. We waited at the top of the stairs in our pajamas, our dog Charlie whining and whimpering in the excitement, until Mother and Dad went downstairs and turned on the tree lights. Once they gave us the go-ahead, we all rushed down to the living room, big kids looking out for little kids, and opened our presents in a frenzy of ripping paper and squeals and barking and the beeping and clanking of new toys.

Someone put Christmas music on the record player.

O little town of Bethlehem/How still we see thee lie./Above thy deep and dreamless sleep/The silent stars go by.

… Our one perfect day of the year.

After presents had been opened, we older girls helped Mother fix a big breakfast of bacon and eggs that we ate in the dining room. The candles on the Advent wreath, changed out from their pink and lavender to red in honor of the day, blazed all morning. There were too many of us to go to church together, so those who hadn’t been to Midnight Mass drifted off to Mass in twos and threes.

From noon on, Christmas changed over to the twins’ birthday. Following family birthday tradition, Ilene didn’t have to help with dishes or set the table, the usual girl chores. Both she and Paul got to laze around in the living room and ask other people to bring them a soda or a glass of juice while they played with their new toys or watched some old movie on TV, which they got to choose. At dinner, while Dad read the gospel from the Christmas Mass, Paul and Ilene got to relight the red candles on the Advent Wreath. Mother carried in the roast beef with great ceremony and placed it in front of Dad, and the twins got their pick of the roast – they usually chose the ends, valuable mostly because there were only two of them – and they were served first. Our ten sequined, red felt Christmas stockings hung from the dining room fireplace mantle. Above them, the little brass angels of the Swedish chimes, pushed by the rising heat of little candles, clanged against bells as they swung by.

Dessert was always the same – two layer-cakes in the shape of a Christmas tree, one white, one chocolate, both of them made from Betty Crocker mixes and decorated with green frosting and little globs of red, blue and yellow frosting made to look like Christmas tree ornaments. After the dinner plates were cleared away, Sheila, Mary Grace or I would go out to the kitchen to light the candles on the cakes. The twins would squirm and grin kitty-corner from each other at the long table. When we gave the signal, Johnny or Patrick would turn off the lights and start the singing and we’d deliver the cakes and birthday presents by the light of all the candles.

Fast forward to today

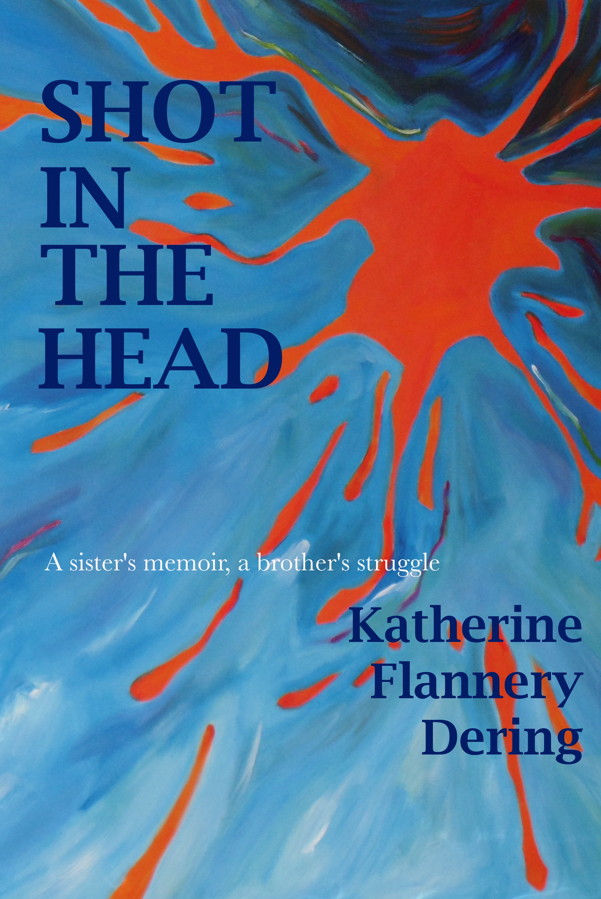

The above is an excerpt from Shot in the Head, A Sister’s Memoir, a Brother’s Struggle, my memoir about my family, and more specifically about taking care of my brother, Paul.

Little did we know back in 1970 when the ten of us posed for this picture – that’s Paul petting our dog, Charlie – how it would all turn out. Our beautiful baby Paul grew into a handsome teenager, full of promise…

…until he succumbed to a psychotic episode at age 16. Christmas was never the same again for our family. Despite frantic efforts to get him psychiatric care, Schizophrenia killed the brother we knew and left in his place a confused, delusional man, who had no more than a few scattered minutes of sanity ever again. And his situation worsened over the years, as most of our psychiatric facilities were closed and fewer and fewer facilities were available for the care of those most seriously ill.

Our system of care for people with serious mental illnesses in our country is simply not working. 4% of our population suffers from a serious mental illness, and many of them, like my brother Paul, never really recover, even if they stay on medication. Only about one-third of people diagnosed with schizophrenia recover, a third cycle in and out, and a third never achieve any appreciable recovery. Many of these are homeless or in jail, due to the lack of appropriate care facilities and supportive housing.

Ilene’s Christmas Birthday Wish

Over the past few years, the families of people like Paul came together and let our congressmen and senators know that we wanted them to end the IMD exclusion, a provision of Medicaid that prohibits providing benefits – i.e. funding – to people being cared for in an “institution of mental disease.” So far, even when the 20th Century Cures Act was passed, it did not address this issue. But although the provision has still not been repealed, Alex M. Azar, Secretary of Health and Human Services has recently released instructions allowing the States to apply for a waiver to the provision, which will allow them to care for seriously mentally ill people in the hospital, if that is what their illness requires. This is a step forward, but not enough. The most seriously ill, like my brother, however, need supportive housing. It is as important a component of their care as their medications. But because of the IMD, long term housing for mentally ill people still cannot include supervisory and medical staff.

A psychiatric nurse who works in a county upstate told me once that they saw the same mentally ill patients cycle onto their ward over and over again. “It’s David again,” they’d say to each other when the call came in that a psychotic man had been brought into the ER. Or Cheryl, or John… They knew what drugs worked the last time, so they’d get him or her stabilized in four or five days, then release them to a taxi with a paper prescription, $25 and one night prepaid in a local motel. They would be back in a month or two.

Hospitalization, stabilization, release, decline,

psychosis, fights, rehospitalization or jail.

No day clinic, no pretense of psychiatric care.

You’re in charge of yourself.

Let someone know if you’re feeling bad.

Nothing to do and no supervision.

300 men and women living in one building,

Delusions, mania, confusion, despair.

Somebody crashes, now there’s another

Police car stops. They’re off with my brother.

Hospitalization, stabilization, release, decline,

psychosis, fights, rehospitalization or jail.

My best wishes to all for a happy and healthy holiday season.

To learn more about schizophrenia and what is needed to improve care for people with serious brain disorders, visit the websites of the Treatment Advocacy Center and/or Mental Illness Policy Org.

To learn more about possible supportive housing options, see my blog with that title on this WordPress address. Let’s make 2020 the year we help the mentally ill homeless off the street and out of hell-hole “adult homes.”